mother’s musings on a manifesto

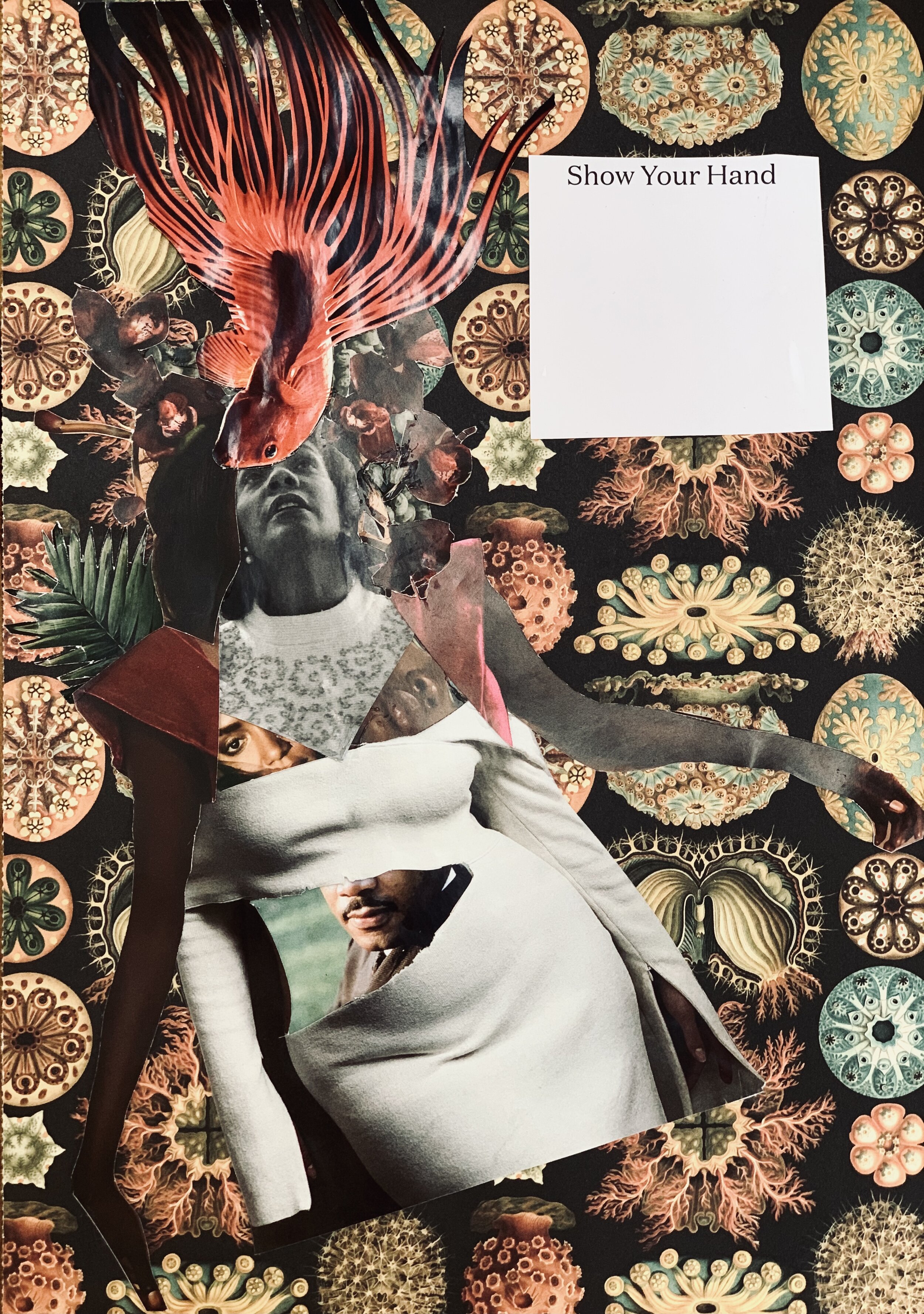

Because our hands have exchanged pamphlets and flyers for political rallies—nervous sweat dampening the paper so that black ink drips past the margins—because our hands have folded church bulletins into the back of black palm-sized bibles; because our hands have pressed perfume, dried flowers, blue paper into used envelopes—signed x so you know it’s me—because of all these works of our hands we imagined turning this manifesto from dream into print. But here we are in digital space still, but not stagnant, not rushing process—because you already know what it is, if you have been here longer than awhile. This is a draft, pushing and pulling Mother Mercy’s language for internal guidance and reflection as well as an offering to those in conversation with us. We worked with scraps of old fabrics, family photos, magazine clippings, and maps alongside text to tell an origin story and to provide a look forward and at present. This is a tale birthed from one daughter and one mother who now are many. So pull up and on through:

“watch as well as pray.”-grandma dee

section one:

we know

we know process is the project.

“A seed is alive while it waits.” - Hope Jahran

Process is the project is a reorientation of ourselves and our approach to art-making and practicing community. It turns away from the pressure to produce, to compete, to burn our spirits out trying to be the shiniest. To understand that process is the project is to acknowledge and take seriously the generative power that lives in the doing of the art and what new dreams and works can be conjured by remaining firmly in the midst of the process rather than speeding to have a “result” that is easily recognizable as such by those we see as audience, spectators, or other people whose approval we may feel we need.

Process is the project is a reminder to pay close attention to method, to the creation of the ideal conditions necessary for us to enter into dreamspace, creative sanctuary, to find the right words, colors, and sounds we need to render our work alive. We work to become so familiar with the how and why. Do you need: pen, pencil, brush, paper—do you prefer lined or plain—acrylic or watercolor, a tablet, a phone, fabric, thread? Maybe there is something you need to do to enter into your personal creative sanctuary: re-reading a passage or a poem; listening to the same song on repeat; taking a walk for some fresh air and some time to call someone you love; a short nap; a deep sleep? Process is the project turns away from the hyper-fixation on glossy “finished products” and refuses the creation of objects and ideas that are easily consumed by and accessible to the same institutions who require our death.

Process is the project does not mean that dedication and turning a painstaking eye to one’s work are compromised. It does not mean that we leave in our wake a trail of half-read books and sentences undone at the seams, nor do we explain away the abandonment of work that still holds so much possibility because the process is all that matters. This conviction asks of us to be diligent and intentional with all the thinking, art-making, theorizing, and all kinds of doing in which we engage while also freeing ourselves from the pressure to break our own spirits because the ends justify the breaking in the meantime. We seek equilibrium—or as close to equilibrium as we can get—taking seriously our selves, our minds, and our imaginations and respecting that art-making is a continuing practice including mistakes, shifting directions, triumphs, and frustrations rather than a race to some neat and discernible end.

we know now is no time to be small; we know it is daunting to expand in a world demanding a flattening of our spirits.

“This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough…” -The Combahee River Collective Statement

We remove ourselves from any circumstances that demand the [mis]use of our bodies, care, time, and artful pursuits solely for shoring up people and institutions who do not care if we die slowly or die tomorrow. Who does it serve for us to bend and fold into the most non-threatening versions of ourselves?

Beyond replenishing the aspects of ourselves which have been depleted by these same people and institutions, we reserve the right to experience and assert the most expansive versions of who we are and the daily upheavals we are capable of inciting. We will not diminish ourselves in life, neither will we do so on the page, on screen, on canvas, nor on wax.

It is especially urgent now, yesterday, in the Black future, 550 years ago, tomorrow at 2pm and in all the infinite, possible timelines that have become necessary for us to chart in order to keep alive. This deadly world continues to require more and more of our time, care, presence, physical capabilities, and peace of mind than we have or are willing to give while shrinking us, flattening our spirits in order to reduce the possibility of rebellion.

section two:

we do

we do earthwork.

“Make it plain.” -Malcom X

Earthwork is what we do to maintain life seen and unseen, tilling the soil of self and the communities we adore, demystifying the concept of finding our purpose. Earthwork explores how to live on land more tangibly and thus charging ourselves and our communities with an energy to design our lives with clarity, deciding the how and what we speak up into life from a knowing in our grounding.

Yes, earthwork is sometimes rooted in the mundane business that keeps us living, yet it is reimagined and repurposed in the incubator with a lens of creativity and art. Yes, it is the daily bathing, eating, remembering, and also the tracking, the analysis, and integrating of it all. Earthwork is a reach towards being rooted without needing said roots to claim.

We say: no land knows me like I know me. Nevertheless, earthwork is a practice in being grounded on land and moving through water; a chance to engage in place and trusting in our belonging–the purpose and the pleasure in being here, wholly. Pushing self further into the present, into presence and passion. It’s a digging in of ones’ heels with knees slightly bent.

we do birth work.

Ultimately it comes down to making yourself and the people who can share it with you, in some way, more themselves, to make you more yourself, to make human beings more themselves, and therefore, by extension, better, stronger, more real. Isn’t this the function of all art? -Notes from Audre Lorde Discussion at Cazenovia Womens Writers Center - Audre Lorde

Birthwork is assisting in making, creating, and thinking; seeing more than two sides for a dear one; holding the periphery of the full picture; remembering that stakes are high. It’s engaging the tension, but not the drama. Being a dressing room where people can try on their most authentic selves and be seen, as well as be seen all the way through.

It’s a commitment to process–one that isn’t always gentle or clear, but trusted nonetheless; holding promise of new lives for ideas and language, and new lives for us all as we embody both. It’s a decentralization of power in the outer world, and an increase of force in the innerworld. Midwifery—bringing forth our babies into community—bring forth a grown-up self into the present and future. And when there isn’t access to a hand to hold through this labor, we make it possible to deliver one's own.

we do breath work.

“The new moon rode high in the crown of the metropolis/shining, like who on top of this? People was hustling, arguing and bustling/ Gangsters of Gotham hardcore hustling/ I'm wrestling with words and ideas/ my ears is picky, seeking what will transmit./ The scribes can apply to transcript, yo/ this ain't no time where the usual is suitable/ tonight alive, let's describe the inscrutable/the indisputable…” -Respiration, Black Star

We inhale air that sometimes chokes from the vents in the buildings we pay too much for, in neighborhoods sinking under the weight of smog. We exhale words that sound like anticipation trying to hush itself in whispers: respite. Recitatif sounds like music and like something you can drink to cool the throat. Respair: I see us taking ten deep inhales, hands pressing into chest and not one exhale followed with pain, only solace.

We need to keep breathing as we build. Strengthen the connection between body and mind, I and you. So we start with breath, always. We draw in that which connects us to all living beings, we push out what is not ours to hold–a spiritual compost. We use breath in transition, a carrying and caring of the moments between the moments, a language offered in the most holy of tones. We are saying: I am here and I know you are too; we say I will wait right here for you. We breathe for our bodies, to support lung and brain function....pressure. We breathe to acknowledge our whole self as we work so the dreams may be full of life and living.

what we mean by work

“as we demand to be heard/ we want you to hear us. we come to you the way leroi jones comes or cecil taylor/ or b.b king. we come to you alone/ in the theater/ in the story/ & the poem. like with billie holiday or betty carter/ we shd give you a moment that cannot be re-created/ a specificity that cannot be confused. our language shd let you know who’s talking, what we’re talkin abt & how we can’t stop sayin this to you. some urgency accompanies the text. something important is going on. we are speakin. reaching for yr person/ we cannot hold it/ we don’t wanna sell it/ we give you ourselves/ if you listen.” -Nappy Edges,pg. 11 - Ntozake Shange

We say this is work not to polarize play, we say work to honor labor, not the banality of it but rather the seriousness and care, to acknowledge that magic and conjuring come with effort and not anointment alone.

We bear witness in all the ways we know that have been life-sustaining; as in have a seat, a cup of tea, and tell me what happened; and also as in what is the work you need to do that you have been running from? Here’s time and space to stop running, to sit and dream and resolve to act as though you know your thoughts and creations are not to be trifled with. We bear witness, as in we clear the way and create the conditions (where necessary and if welcomed) for artists, thinkers, makers—those with whom we practice community—to think, draw, sing, type, weep, breathe, to participate in art-making with care and rigor. This work is unpredictable, it still has principles, based on what we know, do, feel, and will into existence.

When we work we imagine ourselves interdimensionally, beyond 3D, beyond what we have been told is real, perhaps even beyond the myth of universal truths. We push toward the courage to understand what we know about ourselves and eachother. Salves and saving look and feel different in this incubator. We remain curious and committed in our practice of Black liberation, so we aim to be fluid while offering ourselves and our collaborators the rootedness of community.

We reach for conditions of creation that exist outside of exploitation, punitivity, and damaging dynamics of power. We look at harm and harm reduction from the inside out. We speak authentically and beyond what we know as thought-terminating cliches.

section three: we ask

we ask what’s not working?

“And when we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard nor welcomed but when we are silent we are still afraid. So it is better to speak remembering we were never meant to survive.” -A Litany For Survival - Audre Lorde

We commit to consistently ask ourselves (and you), what’s not working...with our artistic practice; our intellectual inquiry; the way we practice community; the way you build relation to people around you; the way you are treated by those people? We go about our work tenderly and with intention, so that even when it comes time to identify that which cannot continue on with us, we do so with the same tenderness. This question welcomes frustration and disappointment without allowing them to turn destructive to self or to what we have made. Holding process and the meantime in high regard means some ways of working and things we have created during that process may not move forward in their full form, though their imprint may remain.

The implication is not that we continue to elevate ideas, methods, or even people who are harmful in any way in an attempt not to discard harshly or unnecessarily. [Re]convening of minds holds multiple possibilities to deepen one’s knowledge of and appreciation for one’s craft and to renew one’s purpose, ensuring that the work is not just for the sake of avoiding idleness, but rather towards our Black liberatory aims.

we ask what are you willing to do?

“Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?… Just so’s you’re sure, sweetheart, and ready to be healed, cause wholeness is no trifling matter. A lot of weight when you’re well.” -The Salt Eaters, p.3 - Toni Cade Bambara

This question is an invitation, a provocation, a call to look outwards at the black world and turn inwards to assess one’s own internal resources. The question might cause discomfort or even an impulse to recoil, but the unease is not the kind that will harm you. This question is not a threat, it is only a reminder that the effects of your [in]action spread far and wide away from you, into the lives of those with whom we practice community and even people we do not know. What are you willing to do to be well, to be free, to live a full and uncompromised life, for what, for who? We know what it means to feel the wear and weight of years of overwork, exploitation, painful memories—not all ours—whose rhythm our limbs and waists have learned to move to.

The kind of caretaking of self and community we need to be well goes beyond momentary delights, though those serve their own purpose. It includes the fundamental belief that like our personhood, our wellness is not individually determined, meaning that we can no longer accept the well-being of a few in exchange for the suffering and perishing of the many. The weight of our wellness is committing to the daily cultivation of our whole selves, and also the bearing up of each other. What are you willing to relinquish so that other people can breathe more easily and can be well? Are there things you believe are rights or entitlements that are actually the results of the exploitation and death of other human beings? What are you willing to change about your “normal?”

we ask what wills you to wake?

Plenty cats be struggling, not hustling and bubbling/it ain't about production, then—what is we discussing?/ When the cock crows, my crop grows/enable me to rock flows/ Striving for perfection ever since I was a snot-nose/ Colossal! True, original b-boy apostle/Standing on the rooftop with the Zulu Gestapo. You think you the shit? Somebody in the wings'll force you to quit/It could be your crew or clique/ or some random kid you smoked buddha with/ consider me the entity within the industry/ without a history of spitting the epitome of stupidity/ living my life, expressing my liberty, it gotta be done properly/ my name is in the middle of equality… -Definition - Black Star

[Alternatively: what are the political, artistic, intellectual, aesthetic engines behind the work we do and the ways we want to open up for other artists, thinkers, organizers? Or simply, why do we keep going?]

The fact that there are young ones doing cartwheels in a front yard on a street somewhere, or climbing a tree behind a house somewhere, and that they will need things to read and watch and observe and listen to ( for comfort, escape, amusement, lesson-learning) in order to create new lives and worlds out of this horrific one. The need to answer the charge laid out in generations of poems, novels, chants, collages, quilts, tattoos, hairdos, ways of tying up scarves to continue to end our dispossession, and to seek retribution where necessary. Alternatively: because writers, artists, thinkers, organizers, birth workers crafted and lived artful, queer lives before us and we want space to do same, and to make it possible for other people to do same.

We have seen what sits on the other side of our wits’ end and there’s nothing there for us. This art is part of what we have to keep body, spirit, and peace in unity, something to look out for in the morning time, something to keep us on the side of the living. We are willed to wake by the need to ensure that the fact of our existence in all its mundane and magnificent ways must be traced over and over until it is permanent record–and you?

section four: we feel

we feel our art-making must reach for beauty and for the fall of the systems crushing us.

“Conquest ushered in such a world-altering rupture, it is almost impossible for the human imagination to fully conceive of the reach of its violence... Conquest is always changing and in flux. It is in continual need of new language and new conceptual tools, which often exist at the margins of reason and require methods found in artistic and creative production.” -The Black Shoals, p.49 - Tiffany Lethabo King

We challenge the notion that beauty is diametrically opposed to thorough analysis around power and dispossession and to the ongoing struggle against colonial, capitalist, patriarchal matrices. Reveling in beauty has been and continues to be a survival strategy, a way of engaging in the earthwork that makes the future we want to inhabit possible in the now. Our bodies must hold breath in order to continue dreaming and singing and reveling in the sunlight of a very particular shine and quality that enters a room on first waking after uninterrupted sleep, so our art and our imaginings must breathe and sustain life. Moving turns of phrase alone will not topple fascist regimes, but we believe firmly in the kind of spiritual sustenance and strategizing that art-making can provide.

At the same time, we understand the constraints of the forms of expression we choose and nurture, and we recognize that many of our tools are the product of violence and dispossession of our kin and of those we endeavor to practice solidarity with across all diasporas and occupied lands. This art does not call itself forth in a vacuum, and the ecstatic experiences we may conjure/craft/create are not enough on their own to justify exploitation and murder of the workers whose hands form the materials we need to do our own work. Our art does not deal only in abstractions or in sewing beautiful veils behind which to obscure the many horrors of this world’s current iteration[s].

When we speak of beauty, we acknowledge the conventional understanding of this phenomenon, confounding, elusive, and even violent if wielded in particular ways against those people and things that are perceived as lacking beauty. Beauty has been judged as a gendered, feminized quality; primarily concerned with adornment of the physical body, concerned with superficial or trivial matters, and so dismissed as inferior to other more worthwhile pursuits. It would be too easy and even irresponsible to ignore the context of beauty as another branch of the capitalist, patriarchal matrix that reaches far and wide in our lives. The shadow of beauty’s violent machinations hangs heavy, yet we endeavor to think about other ways beauty exists and operates, as a “method,” in the words of Christina Sharpe, who admires her mother’s daily practices in making self and making a home, and in the “attentiveness whenever possible to a kind of aesthetic that escaped violence whenever possible--if it is only the perfect arrangement of pins.”

we feel the urgency to steal ourselves away.

“Grace. Is grace, yes. And I take it quiet, quiet, like thiefing sugar.” -In Another Place, Not Here, p.3 - Dionne Brand

In thinking about what it means to experience and enjoy the full breadth of our selves and what it means to take these selves back from the extractive, lethal environments—sometimes they look like factory floors, sometimes they look like hospital corridors, sometimes they look like classrooms and offices recycling stale air—we are also careful not to be reckless with references to the fugitivity and marronage of ancestors who refused slavery and carved out the elusive otherwise right on the same land they had tended to under duress and threat of death at every turn. The conditions of black fugitivity: being forever wanted and hunted, looking over one’s shoulder in anticipation of the wrath of a white world enraged by the audacity of our escape, are too serious and deserve too much care to be rendered as metaphor to serve our own rhetorical purposes.

Nothing that we can fathom, at least on the surface of our consciousness or in our verse or prose, is “like” slavery in both the spiritual and corporeal senses. With this awareness, we prepare to steal ourselves away by seeking guidance and fortitude from our forebears, without trying to make noble our corporate or academic pursuits by drawing hasty parallels between ourselves and those who made us possible. (A working group or a symposium is not a quilombo and it doesn’t have to be described as such for the work to be generative or threatening in some way to racist, capitalist institutions).

In short, we are devising strategies and daily practices to not only deny access to the best of ourselves to an undeserving world, but also to move towards and inhabit an elsewhere where we are far more than what we can be “used” for and what value can be placed on the fruits of our labor.

we will protect.

“Our cosmology may be a little different, as each groups is, so what I want to figure out is how ours is different, how is our concept of evil unlike other peoples’? How is our rearing of children different? How are our pariahs different? A legal outlaw is not the same thing as a community outlaw.” -Black Women Writers at Work, p.129 - Toni Morrision

With force fields and shields, we hold our spirits, restrict access to the self when needed. We expand this field and hold our kin in community. We be a vector in space and time. A personal armour that easily transforms into an extended hand, a hug–love tight and impenetrable. We protect daily, not as if in combat but as in our conjuring and knowing that we are only safe in our own hands. We nourish, we feed in this famine. We know it is by a watering that we sustain the trunk with many a ring. We lack the time, not the range, to settle with close-ranged weaponry. We use our hands in ways we don’t speak of in front of company–and there are hands we are willing to let go of as much as hands we are willing to hold.

We are willing to hold the hands of those who are able to commit to handling other people with care. In our workplaces, our homes, our studios, and our intimate relationships, we have known manipulation and harshness, we have known what it means to be misnamed and unseen. For our art- and world-making to be possible, we must hold each other with tenderness while also holding each other to account, and we can do so without trying to crush each other’s wills and spirits in the name of rigor or “tough love.” We can hold each other’s hands without squeezing bone and tendon too hard to prove our strength. We do not impose fear or violence as a tactic for sharpening one’s thinking and making tools simply because we had to endure ourselves. We are willing to hold the hands of those who take seriously the responsibility of working and making from a grounding within black diasporic thought and artistic bodies of knowledge. We are willing to hold the hands of those who understand that we are operating within a universe already imagined and brought to life on page and screen, in chants and bagged groceries for the kids, and that we aspire to be neither the first that has ever been nor the only that will ever be. We understand that “we were not invented yesterday,” and that precedent and context are not a limitation, but an abundance of work to turn to for comfort and to think alongside and through as we go.

We are willing to let go of hands that believe in community as transaction; hands dealing in solidarity as though it is a loan–I showed up for your protest, you owe me money for my fundraising; hands weighing and valuing self-interest higher than the personhood that is lived and affirmed in relation to the personhood of other people around one’s self. We are willing to let go of the hands of anyone who believes that the urgent needs, marginalizations, and material conditions of anyone’s suffering or oppression are a “distraction” or relatively frivolous or tangential to the task and cause of black liberation. This includes anyone who thinks queerness an aberration, disability a point of shame, poverty a moral failing, anyone who believes that enthroning a few “professional” (read: well-behaved, easily legible in white supremacist codes) black people will improve the now and tomorrow of black communities, even if said occupants of the seats or thrones are causing blood to flow like rain in other black worlds beyond US empire.

we will teach.

“I write because I must. I write because it keeps me going. I probably have not killed anyone in America because I write. I’ve maintained good control over myself by writing. I also write because I think one must not only share what one thinks, or the conclusions one has reached, but one must also share to help others reach their conclusions. Writing might help them survive.” -Black Women Writers at Work,p. 142 - Sonia Sanchez

There are many ways to kill and just as many ways to survive–we are learning beyond both. We are learning and thus teaching ourselves what it means to be alive everyday, to be merciful, to be unabashed– we are learning and thus learning you too. We preach to practice, we trace ourselves over and over again not merely for gallery display but so that kin may track and pick up where we left off, where we might not be able to go. We teach for frame of reference, not merely to be referenced or referential alone. We say write your name in these ashes–that is the lesson; we say keep going as much as stop, to support the learning. We teach to learn new things, to conjure the lessons we need from you. Sometimes it’s the ideas of scholars we share, other times messages in music or from the good book, or those which came up from within after a long day of work. Sometimes it’s recipes or routes, arithmetic — chemistry; we teach what we know and what we’ve been shown by the wealth of communities that still are raising us. We teach the life sustaining and to the death of that which is not.

we will grow.

“Revolution begins with the self, in the self. The individual, the basic revolutionary unit, must be purged of poision and lies that assault the ego and threaten the heat, that hazard the next larger unit—the couple or pair, that jeopardize the still larger unit—the family or cell, that put the entire movement in peril.” -On the Issue of Roles from The Black Woman, p.109 - Toni Cade Bambara

It either grows or it doesn’t–and so we do all we can to.

what we mean by mercy

A reprise, a resumption—an exclamation in fear and surprise making way for fight—mercy is how we fight our flattening and our extermination. Mercy is giving to self unabashedly, not necessarily unapologetically; here, apology is not a submission nor error, it is an empathetic song sung for when mercy is muddled within, a tune especially gifted to our kin. Forgiveness is not ours to define, but we invite the change, death, and rebirth that makes forgiveness and thus mercy possible, fuel for the mending of the violence within, a marker not only of fugitive space but a maroon reality. With mercy, we reach beyond what we have been shown; we remember and make it palpable—our compassion for our many selves and the collective is grown from steady practice, not the principle alone.